On Friday night at Summerstage in Central Park, under a cloudless sky in which stars became gradually visible, the singer Martha Wainwright and the dance troupe Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company shared a program (repeated on Saturday). As my companion remarked, the first half felt like a Martha Wainwright concert with some dances tacked on. The second half, however, became more substantial in terms of both dance and Ms. Wainwright’s music.

Charmingly assured and no-nonsense, the blond Ms. Wainwright delivered song upon song. When she was not leading her musicians (who on Friday included her husband, Brad Albetta; her mother, Kate McGarrigle; and her cousin Lily Lanken) in her own songs, she led them in numbers ranging from Vaughan Williams to Annie Lennox.

In both voice and music, her span includes country and blues; and her singing has sometimes a chesty blues intensity, sometimes youthful country innocence, with ascents into falsetto half-voice and a deliberate use of breathiness and vocal cracks as part of the expressive mix. This is singing that relies on a marked use of mannerism. But it’s also real singing, in which the voice itself, musically, is often very directly affecting.

Her diction varies: in some of her own songs you could lose track of the words, but never for an instant in “Stormy Weather.” This classic song came in the middle of Part 2, and found Ms. Wainwright at her most intense and also, in phrasing, at her most personal. Having reached that peak, she stayed there for the world premiere of her own “Tears of St. Lawrence,” walking through Edwaard Liang’s and Christopher Wheeldon’s choreography at the beginning and the end.

Traditionally the tears of St. Lawrence are the meteor showers that may occur around St. Lawrence’s Day (Aug. 10). The new ballet ended with the dancers and Ms. Wainwright each extending an arm diagonally to the sky, holding what looked like a star.

The program says, “All choreography, music, and lighting are by Edwaard Liang, Christopher Wheeldon, Martha Wainwright, and Mary Louise Geiger, respectively, unless otherwise noted.” The “respectively” caused confusion. So, to Wheeldon followers, does the fact that only one item, “Tears,” is called a world premiere. (Summerstage had commissioned both the score and the dance.) On checking, I find that everything except Mr. Wheeldon’s “Fool’s Paradise” (2007) was having its premiere on Friday, and that all choreography was by Mr. Wheeldon except the dance quintet “Bleeding All Over You,” credited just to Mr. Liang, and “Tears,” which was by both men. Can’t Summerstage take more trouble over these matters?

An added minor confusion was the spelling of the duet printed as “Whither Must I Wander,” which is how Robert Louis Stevenson spelled the words and how Ralph Vaughan Williams spelled the title when he composed one of his “Songs of Travel.” Ms. Wainwright, however, spells it “Wither Must I Wander” on a CD, and that’s how Morphoses presented a preview performance of it this month in Vail, Colo. I don’t mind calling them Mr. Weeldon and Ms. Whainwright until they can decide wat’s wat. (The pas de deux features Wendy Whelan and Edward Watson, or possibly Whendy Welan and Edwhard Whatson.)

The first dances — the solo “Far Away” for Rory Hohenstein, the “Whither” duet, Mr. Liang’s quintet “Bleeding All Over You” (for Teresa Reichlen and four men), and the duet “Love Is a Stranger” (for Tiler Peck and Gonzalo Garcia) — are all somewhat slick. Mr. Liang plays such organizational games with the men of “Bleeding” that for a while on Friday I lost all concentration on Ms. Reichlen. She had the best moment, though, as she advanced upstage away from the audience, addressing Ms. Wainwright eye to eye, sister to sister. And her authority and stretch were real pleasures, the grandest solo dancing of the evening.

In the “Far Away” solo and the two duets you can see Mr. Wheeldon’s clear way of structuring a dance into separate phrases, the sheer polish that lets you know that every movement has been choreographed, and the sensitivity to dancers. Almost invariably, each performer looks focused, attractive, sincere. But there’s often too much end-stopping to the phrasing; you seem to see where dancers and choreographer took their coffee breaks and then came up with a new idea.

Does the sharp contrast between one phrase and the next demonstrate stylistic skill or expressive incoherence? I like the control with which Mr. Wheeldon keeps making you pay attention, but I can’t get interested in these dances as thought or drama. And the way that some of the phrases rely on repeated upper-body gesture — what ballet people call a demi-character emphasis — has a cuteness (in some places) or obviousness (in others) that diminishes their effect as dance, as if trying to tell us What’s on These People’s Minds.

The two duets, “Fool’s Paradise” and “Tears of St. Lawrence,” also show how seldom Mr. Wheeldon can ever let dancers register as soloists. Even when they’re not partnering each other (as they do most of the time), these dancers tend to keep addressing or moving in unison with one another.

“Fool’s Paradise” has some striking quotations and derivations from Frederick Ashton’s “white” pas de trois, “Monotones,” which is (as Mr. Wheeldon acknowledges — Morphoses has danced it) an all-time summit of pure classical adagio dancing. Mr. Wheeldon has learned much about how Ashton connects one dancer’s line with another’s, the compositional wit with which, in a trio, one woman’s supported pirouette is echoed by a man’s unsupported pirouette, and other beauties. But he can almost never expand a pas de trois (as Ashton often does) across the whole stage to show these people as individuals and the drama of space. In duets his couples are never at opposite purposes. They’re always working in intricate combination, and the men get to do mighty little dancing beneath the waist.

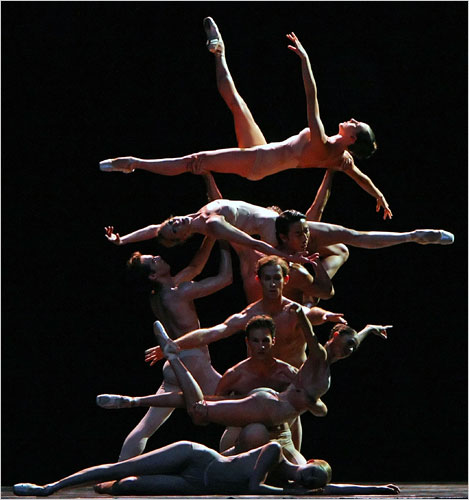

“Fools’ Paradise” (set to taped music by Joby Talbot, the only work not played by Ms. Wainwright) and “Tears of St. Lawrence” both illustrate Mr. Wheeldon’s compositional skills. The big vertically ascending tableau with which “Fools” ends is a wow effect that might make any choreographer proud.

Against a setting of five male-female couples, “Tears” emphasizes the two men, Mr. Hohenstein and Mr. Watson. At first you think they may be a gay couple: the ballet starts with them doing the same lifts as the others, but in the foreground. Later, though, they’re separated and undergo separate adventures, some involving individual women.

Mr. Hohenstein does have a solo, which tries hard (gesturally) to communicate some brief drama, but it’s vague and soon forgotten. Overall, the choreography — which includes another “Monotones” reference — attends principally to partnering and pattern. On first acquaintance its expressive and stylistic limitations stop me from doing credit to its obvious compositional accomplishment.